Biography

Since the 1960’s Klaus Rinke has played an important part in the international art scene. His work is integral to the radical artistic movements that emerged during that period, which include Performance Art, Body Art, Land Art, Conceptual Art, Process Art and Action Art.

Among the multitude of exhibitions spanning his long artistic career, Rinke has twice been represented at Documenta Kassel and twice at the Biennale of Venice. He has been featured in solo shows at MOMA in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern in London and the Haghia Sophia in Istanbul Turkey. Rinke is the recipient of numerous awards and honors including the French Minister of Culture’s prestigious Medal of the Chevalier Des Arts et des Lettres. His work is represented in over 66 museums and public collections throughout the world.

Rinke is credited with creating the renowned “Düsseldorf Scene.” In 1968 Rinke conceived of the idea to unite the young Düsseldorf artists for an exhibition at the Kunst Museum Lucerne along with art historian Jean Christophe Ammann. The show was entitled “The Düsseldorf Scene.” The artists originally featured in the show included Joseph Beuys, Jörg Immendorf, Imi Knoebel, Blinky Palermo, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richer, and Klaus Rinke.

In his body of work, Rinke explores his concern with the concepts of “duration” and impermanence. To define these concepts, he employs both clocks and water. In 1967 Rinke described water as a “sculptural” material, explaining the process of ladling water into containers as a means to measure time and as a “radical intervention into nature.”

“I found that water was a sculptural material. In handling water I concluded that filling up a sculpture with water takes time. A ton, how long to fill it up? How long to empty?”

Rinke uses the element of water as a universal symbol of femininity and fertility, purification and flux, often focusing on the evaporation of water to depict its impermanence. In his art he emphasizes water as an essential element focusing on it’s importance to life and human well being. His work with water also serves to highlight his environmental concerns emphasizing the fragility, scarcity and interconnection of our global water sources.

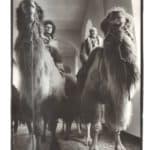

In the mid 1960’s Rinke developed his “Primary Demonstrations” in which he explored the concepts of “masculine and feminine” and the spatiality and temporality of human existence. In these seminal performances, Rinke used his own body and gestures to configure “drawings in space” as a means to measure space and time. These actions took place in nature, galleries or museums. To accompany the movements of his body, Rinke often employed railway clocks and plum bobs. The clocks were meant to represent instruments made by human beings, symbolizing “universal time.” The plum bobs, bobs of lead hanging vertically from plum-lines pointing towards the earth, symbolized the gravity of a point in space or “being earthbound.”

From 1969 to 1976, along with his performances and body art, his work centered on photography where he again incorporated his fascination with time:

“I made endless black and white photographs of the surfaces of the ocean, cut into like a surgeon, one-sixtieth of a second of the surface’s infinite movement.”

Rinke’s work eventually evolved to include installations, and sculptures or “philosophical instruments” made of tin, stainless steel and other metals, “sculptural” paintings and graphite drawings, which he considered elemental to his artistic expression. In a quest for universal and primary sources, Rinke spent long sojourns in Australia with the Aborigines. In Aboriginal art he found a connection to his abstract drawings of the 1950’s and 1960’s, which reflect anthropomorphic, curvilinear and organic shapes culminating in a unique, “primordial alphabet.” These are not drawings in any classical sense, but minimalist abstractions more closely located to the discourse of sculpture. His transcendent and universal archetypical forms highlight, as he notes, the “rhythms of day and night, the echo of a time when things were still a unity.”

Rinke’s unique aesthetic search has brought him to the frontier of art and science. He has created his own iconography as he has investigated the metaphysics and the relativity of time from his “time drawings,” sculptures and photographs to his installations and performances. Graphite, a material representing the industrial Ruhr valley where he grew up, water, plum bobs to measure gravity, and railroad clocks to measure time have emerged as leitmotifs in his works. His research into the relativity of time is evident in sculptures such as “Albert Einstein, When Stops Baden-Baden at this Train,” consisting of a large illuminated railway clock on wheels set on railway tracks which moves bidirectionally.

“My father was a railway man, my grandfather was a railway man, and my great grand father was a railway man” says Rinke, who was born in Wattenscheid, Germany in 1939 and educated at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen, Germany. “As a child I grew up near a railway station with numerous railway clocks. At night the clocks became my moons. Early on I incorporated these clocks into my life. Later in my 20’s and early 30’s the German railway clock and the notion of time and duration would become a major factor in my artistic expression.”

Rinke’s body of work symbolizes the defining aspects of human existence, man’s relationship to the essential elements of our world: space and gravity, using elementary structures in which water, graphite and metal predominate.

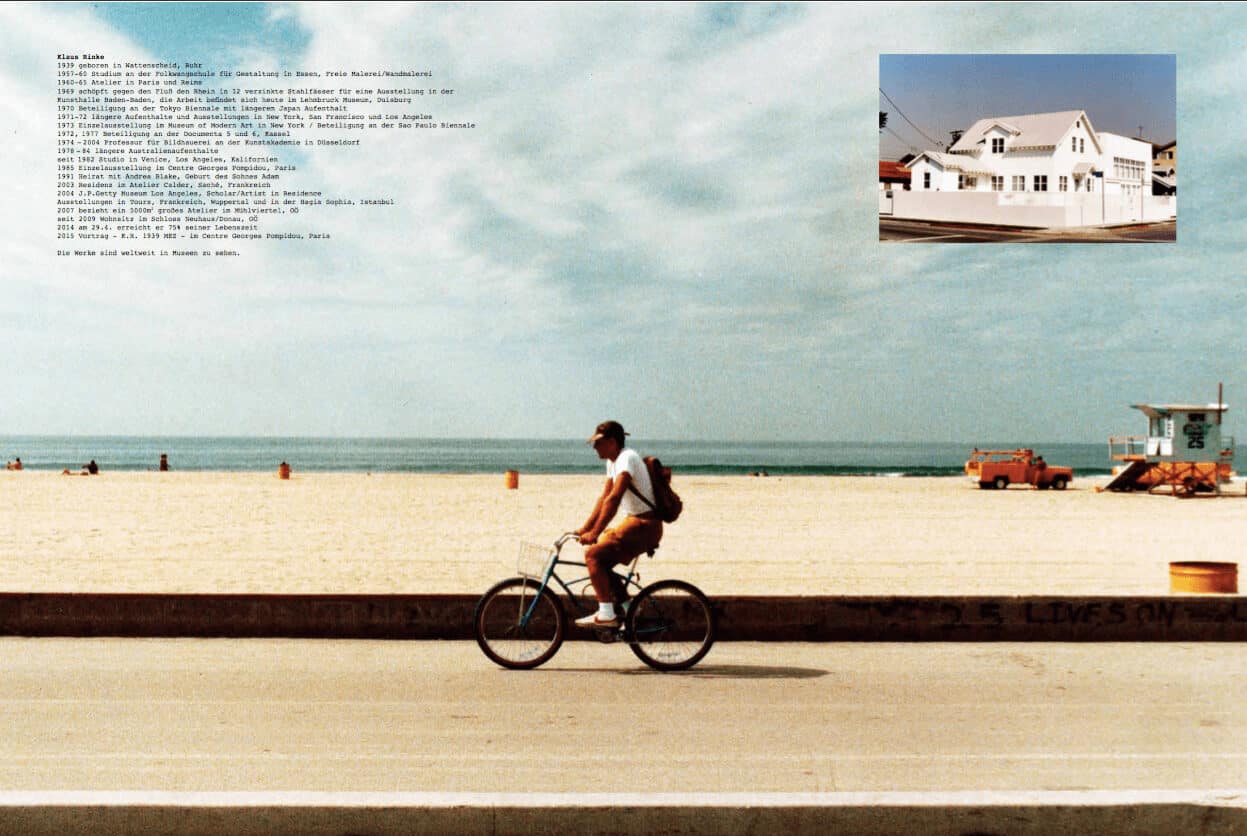

Rinke lives and works between Neuhaus, Austria and Los Angeles, California.